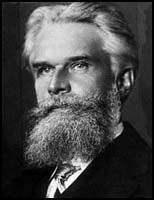

Havelock Ellis

His father was rarely home and it was his mother who was the dominant influence in his early life. According to one of his biographers: "As an ardent evangelical Christian, who had experienced a conversion at the age of seventeen, she had vowed never to visit a theatre in her life. Despite this she was a warm influence on the young Ellis, who early on slipped away from the more rigid aspects of her faith." Havelock Ellis was provided with a basic education at local schools but he was a compulsive reader and he was deeply influenced by the philosopher, Ernest Renan, and the poets, Percy Bysshe Shelley and Algernon Charles Swinburne.

He travelled with his father to Australia and at the age of nineteen became a teacher in schools in the outback. During this period he read Life in Nature by James Hinton, a writer on political, social, religious, and sexual matters. He later recalled that the book sparked a spiritual transformation: "The clash in my inner life was due to what had come to seem to me the hopeless discrepancy of two different conceptions of the universe … The great revelation brought to me by Hinton … was that these two conflicting attitudes are really but harmonious though different aspects of the same unity." Ellis now became convinced that sexual freedom could bring in a new age of happiness.

Havelock Ellis arrived back in England in April 1879 and eventually became a medical student at St Thomas's Hospital in Southwark. In 1883 he joined the Fellowship of the New Life, an organisation founded by Thomas Davidson. Other members included Edward Carpenter, Edith Lees, Edith Nesbit, Frank Podmore, Isabella Ford, Henry Hyde Champion, Hubert Bland, Edward Pease and Henry Stephens Salt. According to another member, Ramsay MacDonald, the group were influenced by the ideas of Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson.

In January 1884 some of the members of the group, including Havelock Ellis, decided to form a socialist debating group. Frank Podmore suggested that the group should be named after the Roman General, Quintus Fabius Maximus, who advocated the weakening the opposition by harassing operations rather than becoming involved in pitched battles. They therefore decided to call themselves the Fabian Society.

Havelock Ellis read the novel Story of an African Farm at the beginning of 1884. He wrote in his autobiography, My Life (1940): "What delighted me in The African Farm was, in part, the touch of genius, the freshness of its outlook, the firm splendor of its style, the penetration of its insight into the core of things." Ellis wrote to the author, Olive Schreiner and she replied on 25th February 1884: "The book was written in an upcountry farm in the Karoo and it gives me great pleasure to think that other hearts find it real." Soon afterwards they arranged a meeting and over the next few months they were constant companions.

Phyllis Grosskurth, the author of Havelock Ellis (1980), has argued: "Ellis and Olive were completely devoted to each other. They went to meetings and lectures together; they wandered through art galleries; late at night after the theatre they would stroll along the street, the tall, lean youth and the short, squat girl holding hands and chattering endlessly in a carefree way." They both shared the same views on sexuality, free love, marriage, the emancipation of women, sexual equality and birth control.

Ellis later wrote in his autobiography, My Life (1940): "She was in some respects the most wonderful woman of her time, as well as its chief woman-artist in language, and that such a woman should be the first woman in the world I was to know by intimate revelation was an overwhelming fact. It might well have disturbed my mental balance, and for a while I was almost intoxicated by the experience." However, he added: "We were not what can be technically, or even ordinarily, called lovers. But the relationship of affectionate friendship which was really established meant more for both of us, and was even more intimate, than is often and relationship between those who technically and ordinarily are lovers."

According to Jeffrey Weeks: "Olive was a forceful and passionate woman, though prone to ill health, and the two writers quickly established a fervent relationship. It is not clear whether it was conventionally consummated. Ellis himself appears not to have been strongly drawn to heterosexual intercourse, and had a lifelong interest in urolagnia, a delight in seeing women urinate."

Olive also became friends with Karl Pearson, the Goldsmid Chair of Applied Mathematics and Mechanics at University College. By 1885 she was in love with Pearson and he began to replace Havelock Ellis in the role of confidant. However, he did not feel the same way about her. Olive wrote that while she was desperately in love, he was "too idealistic for anything as earthy as sex." He later married Maria Sharpe and their relationship came to an end.

Olive Schreiner remained close to Ellis but was upset by his lack of sexual desire. She wrote to Edward Carpenter: "Ellis has a strange reserved spirit. The tragedy of his life is that the outer man gives no expression to the wonderful beautiful soul in him, which now and then flashes out on you when you come near him. In some ways he has the noblest nature of any human being I know."

By March 1884 the Fabian Society had twenty members. However, over the next couple of years the group increased in size and included socialists such as Sydney Olivier, William Clarke, Eleanor Marx, Annie Besant, Graham Wallas, J. A. Hobson, Sidney Webb, Beatrice Webb, George Bernard Shaw, Charles Trevelyan, J. R. Clynes, Harry Snell, Clementina Black, Walter Crane, Sylvester Williams, H. G. Wells, Clifford Allen and Amber Reeves.

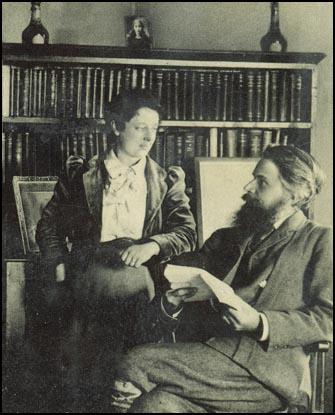

Havelock Ellis met Edith Lees, in 1887 at a meeting of the Fellowship of the New Life. He later recalled: "She was a small, compact, active person, scarcely five feet in height, with a fine skin, a singularly well-shaped head with curly hair, square, powerful hands, very small feet, and - her most conspicuous feature on a first view - large rather pale blue eyes. I cannot say that the impression she made on me on that occasion was specially sympathetic; it so happens that the dominating feature of her face, the pale blue eyes, is not one that appeals to me, for to me green or grey eyes (I believe because one is drawn to those of one's own type) are the congenial eyes, and I never grew really to admire them, though to many they were peculiarly beautiful and fascinating." Edith was also critical of Havelock's appearance. "She (Edith) was not impressed; it seemed to her that my clothes were ill-made, and that was a point on which she always remained sensitive."

In 1890 Havelock Ellis' first book, The New Spirit, was published. According to one critic, the book discusses "the manifestations of the new spirit abroad in the world: the growing sciences of anthropology, sociology, and political science; the increasing importance of women; the disappearance of war; the substitution of art for religion as a social and emotional outlet." The book was heavily criticised. One reviewer commented that: "His reading has been rather too exclusively among the rebels and heretics of literature; and he would be well advised if he were to restore the balance by devoting more attention to the older, more conservative, more historic writers, whose influence, we may depend upon it, will survive the fame of several of the new men for whom our present-day critics are erecting very lofty pedestals."

Edith Lees later wrote: "When I first read The New Spirit, I knew I loved the man who wrote it." In August, Ellis had a week's work replacing Dr. Bonar at Probus, in Cornwall. While Lamorna he met Edith Lees who was on holiday at the time. They went for long walks together and talked a great deal about their ideas on politics and religion. Ellis later described their relationship as "a union of affectionate comradeship, in which the specific emotions of sex had the smallest part, yet a union, as I was later to learn by experience, able to attain even on that basis a passionate intensity of love."

They eventually married on 19th December 1891. The relationship was highly unconventional. They maintained separate incomes and, for large parts of the year, separate dwellings. It seems that they did not have a sexual relationship. Ellis wrote that "on my side I felt that in this respect we were relatively unsuited to each other, that (sexual) relations were incomplete and unsatisfactory". Lees was a lesbian who had relationships with other women. The first relationship was with a woman that Ellis called "Claire" in his autobiography. Phyllis Grosskurth has pointed out: "Edith was to have a succession of passionate relationships, although - and Ellis regarded this as an extenuation - only one intense friend at a time. He learned to accept the succession of dear friends; he never quarrelled with any of them and the only test he applied to them was whether they were good for Edith or not."

In his autobiography, My Life: Havelock Ellis claimed: "It was certainly not a union of unrestrainable passion; I, though I failed yet clearly to realise why, was conscious of no inevitably passionate sexual attraction to her, and she, also without yet clearly realising why, had never felt genuinely passionate sexual attraction for any man... Whatever passionate attractions she had experienced were for women."

Havelock Ellis published his second book, The Nationalization of Health in 1892. Phyllis Grosskurth has commented that Ellis argued: "The state was to be responsible for the physical well-being of the individual, a revolutionary suggestion in its time. Against an historical background of the development of health movements, he discusses the role of the private practitioner, the existing hospital system, the hospital of the future, and the necessity for a Minister of Health... In The Nationalization of Health a national health scheme is, as far as I know, advocated for the first time."

In 1894 Ellis published Man and Woman: A Study of Human Secondary Sexual Characters. In his autobiography he wrote "it was a book to be studied and read in order to clear the ground for the study of sex in the central sense in which I was chiefly concerned with it". He added that it was "primarily undertaken for my own edification". However, as the author of Havelock Ellis (1980) has pointed out: "Until his marriage to Edith, Olive Schreiner seems to have been the only woman with whom he indulged in sexual intimacies, however unsatisfactory they may have been. In other words, the man who wrote Man and Woman was almost totally inexperienced, and when he departs from physiological description he sounds remarkably naïve."

In 1897 Havelock Ellis published Sexual Inversion, the first of his six volume Studies in the Psychology of Sex. The book was first serious study of homosexuality published in Britain. It was based partly as a result of his awareness of the homosexuality of his wife and friends such as Edward Carpenter. Ellis admitted in his autobiography: "Homosexuality was an aspect of sex which up to a few years before had interested me less than any, and I had known very little about it. But during those few years I had become interested in it. Partly I had found that some of my most highly esteemed friends were more or less homosexual (like Edward Carpenter, not to mention Edith)." According to a letter he wrote to Arthur Symonds, Edith Lees Ellis promised to "supply cases of inversion (homosexuality) in women from among her own friends."

Phyllis Grosskurth has argued: "Sexual Inversion was an unprecedented book. Never before had homosexuality been treated so soberly, so comprehensively, so sympathetically. To read it today is to read the voice of common sense and compassion; to read it then was, for the great majority, to be affronted by a deliberate incitement to vice of the most degrading kind.... That such sexual proclivity is not determined by suggestion, accident, or historical conditioning is apparent, he argues, from the fact that it is widespread among animals and that there is abundant evidence of its prevalence among various nations at all periods of history."

As one biographer, Jeffrey Weeks, pointed out: "Ellis's aim was to demonstrate that homosexuality (or inversion, his preferred term) was not a product of peculiar national vices, or periods of social decay, but a common and recurrent part of human sexuality, a quirk of nature, a congenital anomaly." This idea was repugnant to most people and the book was attacked by most reviewers. The birth-control campaigner, Marie Stopes, described reading it as "like breathing a bag of soot; it made me feel choked and dirty for three months."

George Bedborough, the secretary of the Legitimation League, was arrested on 31st May 1898 and charged with selling Sexual Inversion. The arresting officer, John Sweeney, later admitted that the objective was to destroy what they believed was an anarchist organisation as well as removing obscene books for sale: "we were convinced that we should at one blow kill a growing evil in the shape of a vigorous campaign of free love and Anarchism, and at the same time discover the means by which the country was being flooded with books of the psychology type." Bedborough was charged with having "sold and uttered a certain lewd wicked bawdy scandalous and obscene libel in the form of a book entitled Studies in the Psychology of Sex: Sexual Inversion."

A group including George Bernard Shaw, Henry Hyndman, Frank Harris and George Moore, formed a committee to defend the book. Shaw argued: "The prosecution of Mr. Bedborough for selling Mr. Havelock Ellis's book is a masterpiece of police stupidity and magisterial ignorance... In Germany and France the free circulation of such works as the one of Mr. Havelock Ellis's now in question has done a good deal to make the public in those countries understand that decency and sympathy are as necessary in dealing with sexual as with any other subjects. In England we still repudiate decency and sympathy and make virtues of blackguards and ferocity."

In court the book was described as being a "certain lewd, wicked, bawdy, scandalous libel". The judge told George Bedboroug: "So long as you do not touch this filthy work again with your hands and so long as you lead a respectable life, you will hear no more of this. But if you choose to go back to your evil ways, you will be brought up before me, and it will be my duty to send you to prison for a very long time." As a result of this case all copies of Sexual Inversion were withdrawn from sale.

In 1898 Edith Lees Ellis published her first novel, Seaweed: A Cornish Idyll. Havelock Ellis commented that the novel was "a real work of art, well planned and well balanced, original and daring, the genuinely personal outcome of its author, alike in its humour and its firm, deep grip of the great sexual problems it is concerned with, centering around the relations of a wife to a husband who by accident has become impotent.... it has seemed to me that the story was consciously or unconsciously inspired by her own relations with me and of course completely transformed by the artist's hand into a new shape."

During this period Edith began a relationship with Lily, an artist from Ireland who lived in St. Ives. In his autobiography, My Life, Ellis pointed out that: "Much as Edith always admired the clean, honest, reliable Englishwoman, there was yet, as I have already indicated, something in that type that was apt to jar on her in intimate intercourse; she craved something more gracious, less prudish, pure by natural instinct rather than by moral principle. In Lily she found the ideal embodiment of all her cravings." He claimed that he did not mind Edith's passionate relationship with Lily because Claire had absorbed all his capacity for jealously. Edith was devastated when Lily died from Bright's Disease in June 1903.

Havelock Ellis continued to work on Studies in the Psychology of Sex. Volume II, The Evolution of Modesty, The Phenomena of Sexual Periodicity, Auto-Erotism, appeared in 1899. This was followed by Love and Pain, The Sexual Impulse in Women (1903), Sexual Selection in Man (1905), Erotic Symbolism, The Mechanism of Detumescence (1906) and Sex in Relation to Society (1910).

Bertrand Russell wrote to Ottoline Morrell after the final volume was published: "I have read a good deal of Havelock Ellis on sex. It is full of things that everyone ought to know, very scientific and objective, most valuable and interesting. What a folly it is the way people are kept in ignorance on sexual matters, even when they think they know every-thing. I think almost all civilized people are in some way what would be thought abnormal, and they suffer because they don't know that really ever so many people are just like them."

In Erotic Symbolism, The Mechanism of Detumescence Havelock Ellis discussed his "own germ of perversion" urolagina: "There is ample evidence to show that, either as a habitual or more usually an occasional act, the impulse to bestow a symbolic value on the act of urination in a beloved person, is not extremely uncommon; it has been noted of men of high intellectual distinction; it occurs in women as well as men; when existing in only a slight degree, it must be regarded as within the normal limits of variation of sexual emotion."

In December 1914 Havelock Ellis received a letter from Margaret Sanger. As Phyllis Grosskurth, the author of Havelock Ellis (1980), has pointed out: "He invited her to tea the following week and was startled to find her so pretty and so comparatively young. At first she was overwhelmed by his patriarchal beauty and his refusal to make small talk. She was also surprised - as many others were on first meeting him - by his thin, high voice, so unexpected in a man of his size."

Sanger fell in love with Ellis. She wrote in An Autobiography (1938): "I was at peace, and content as I had never been before... I was not excited as I went back through the heavy fog to my own dull little room. My emotion was too deep for that. I felt as though I had been exalted into a hitherto undreamed-of world."

Soon afterwards Sanger tried to turn it into a sexual relationship. Ellis wrote to her explaining "What I felt, and feel, is that by just being your natural spontaneous self you are giving me so much more than I can hope to give you. You see, I am an extremely odd, reserved, slow undemonstrative person, whom it takes years and years to know. I have two or three very dear friends who date from 20 or 25 years back (and they like me better now than they did at first) and none of recent date."

Edith Lees Ellis suffered from poor health in her forties. In March 1916 she suffered from a severe nervous breakdown and entered a local convent nursing home at Hayle in Cornwall. Soon afterwards she attempted suicide by throwing herself from the fourth floor. Havelock Ellis wrote to Edward Carpenter: "Quite what she was feeling and thinking these last few days I do not know. It was some kind of despair. She has been despondent and self-reproachful as not having lived up to her ideals for some time past, and has lost her faith in things and in her spirit... The condition has been fundamentally neurasthenia, with mental symptoms - distressing loss of will power and helplessness."

Edith was eventually released but was forced back to hospital and died of diabetes in September 1916. Havelock Ellis told Margaret Sanger: She was always a child, and through everything, a very lovable child, to the last. Even friends whom she only made during the last few weeks are inconsolable at her loss." Two years later he arranged for the publication of her James Hinton: a Sketch (1918).

Françoise Lafitte-Cyon had been doing some translating work for Edith shortly before her death. Havelock first met her to pay an outstanding bill. They began meeting and on 3rd April 1918, Françoise, who was twenty years his junior, declared her love for the older man. Havelock wrote back that "I feel sure that I am good for you, and I am sure that you suit me. But as lover or a husband you would find me very disappointing." Havelock's relationship with Françoise blossomed. Stella Browne wrote to Margaret Sanger that "Ellis is looking better than I've seen him for some time: he seems slowly recovering from all he had to go through last year." They eventually moved into a cottage in Wivelsfield Green.

Havelock wrote to Françoise Lafitte-Cyon about her death: "I have for a very long time been reconciled to the idea of her (Olive Schreiner) death for I knew for many years her health had been undermined and how much she suffered. I am sure she was quite reconciled herself, though still so full of vivid interest in life, that she went back to Africa to die... It is the end of a long chapter in my life & your Faun will soon be left alone by all the people who knew him early in life."

In 1920 William Heinemann asked Ellis to write a preface for the German best seller, The Diary and Letters of Otto Braun. He was a poet and scholar who had been killed during the First World War. He was visited by Ella Winter, the translator of the book. She wrote in her autobiography, And Not to Yield (1963): "He was an astonishing old man, extremely tall and imposing, with a large head, white hair, and a bushy square beard. He lived alone in a small flat and, to my surprise, made the tea and carried in the tray." Ellis told her: "My wife lives in another flat, we feel that's better for our relationship." Winter pointed out: "When he discussed marriage, I kept very still lest he stop, but I was uncomfortable because he kept his eyes glued on the opposite wall and did not look at me. He developed this habit, I supposed, when he interviewed women about their sex lives for his Psychology of Sex. Presumably one talked more freely that way, but it gave me an eerie feeling. He did not ask me about my sex life. I was rather hurt."

Havelock Ellis published several more books including The Erotic Rights of Women (1918), The Philosophy of Conflict (1919), The Dance of Life (1923), Eonism and Other Supplementary Studies (1928), Fountain of Life (1930), The Revaluation of Obscenity (1931), The Psychology of Sex (1933), Questions of Our Day (1936) and Morals, Manners and Men (1939).

Havelock Ellis died at Cherry Ground, Hintlesham, near Ipswich on 8 July 1939. His autobiography, My Life, was published posthumously during the Second World War in 1940. His biographer, Phyllis Grosskurth, has pointed out: "It was a great disappointment in terms of sales or critical reception. In 1940 people's minds were too preoccupied with the war to pay much attention to it and the reviews tended to be either patronizing or outraged by the accounts of Edith's lesbianism and Ellis's urolagnia."

No comments:

Post a Comment