1951,saw

the forceful emergence of Charles de Gaulle’s RPF with 21.7% of the

popular vote. However, less than five years later, the Gaullist

movement which had marked French politics since 1947 was, by all

accounts, practically dead. Yet, only a bit more than two years

later, Gaullism was resurgent with the birth of the Fifth Republic.

After the RPF in 1951, the novelty of 1956 was the emergence of the

Poujadiste movement (mouvement

Poujadiste),

named after its founder, Pierre Poujade. Its emergence marks the

first post-war far-right movement to grow in France, and the first

far-right movement in the ‘modern’ sense – that is, rid of its

pre-war monarchist or elitist-nationalist overtones. Its emergence,

however, is all the more puzzling given that the years 1953 to 1955

were, in the most part, synonymous with economic growth, rapid

development and also the stabilization of prices following the

inflationist years which had directly succeeded the end of

the war. Usually, it is economic instability and recession which has

allowed for the emergence of the far-right in France.

France

in the post-war era, like most of western Europe, was undergoing

rapid economic transformations, the most notable of which were

urbanization and a shift away from family businesses or farms. The

primary victims of the rapid economic changes were individual farmers

(agriculteurs)

and small shop-owners (artisans

et commerçants).

As a kind of petit bourgeois, the shopkeeper or merchant is at the

confines of the middle and lower classes, not entirely bourgeois like

those above him but not entirely working-class (or populaire) like

those below him. In a certain way, he is constantly fearful of

proletarization or déclassement. In

this vein, the shopkeeper, merchant or small-town employee –

republican, egalitarian and fiercely individualistic – have always

been wary of socio-economic changes which always threaten to crush

him. He is not a capitalist like the upper or middle bourgeoisie,

because he feels his way of life threatened by the “aggressive

capitalism”. He is not either a natural revolutionary, because he

resents ‘proletarization’. Unsurprising, therefore, that these

instinctively conservative (in the pure sense of the term) and

individualistic voters should offer a natural breeding ground and

captive clientele for all sorts of populist conservatives, the

Georges Boulanger of times past and the Le Pens of today.

1956

was a period of rapid economic growth in France, especially with the

emergence of large commercial surfaces, supermarket and price-point

retailers – known in France in 1956 as theprisunic (equivalent

of dollar stores in North America). Supermarkets and price-point

retailers were a direct threat to small-town shops, with the

individual butcher stop, the bakery or the delicatessen. Besides

these broader factors and the social psyche, there was a key

contextual factor at work here in 1956.

In

1953, Antoine Pinay’s government had succeeded in dramatically

reducing inflation – from 12% in 1952 to -1.8% in 1953, then

0.5%-1% in 1954 and 1955. Inflation had been high in the post-war

era, peaking at 59% in 1948 and never dropping any lower than 10-11%.

The main benefactor of inflation was the small shopkeeper, who

amassed more and more wealth and cared much less about taxes given

that it was paid with depreciating money. These businesses had

benefited spectacularly from inflation, but they had failed to adapt

to modern economic conditions of retail. The Poujadist movement was

the child born of deflation and the stabilization of prices.

The

traditional literature treats the birth of Poujadism as an anti-tax

revolt (révolte

du fisc),

but the tax revolt which started brewing in 1953 was more

the reason of

Poujadism’s birth than its deep cause. Inflation

had made taxes bearable, deflation made them unbearable. A state of

affairs intensified by the government’s “fiscal Gestapo” which

strictly enforced the collection of taxes. The Union

de défense des commerçants et artisans (UDCA)

was created in 1953, as a corporatist union founded by Pierre

Poujade, a stationer from Saint-Céré (Lot), with his great oratory

talents and room-filling charisma.

Derided

as fascist, true in part, it is fairer and better to view the UDCA

was a defensive reaction by small-town shopkeepers, merchants and

small farmers who were attached to the founding republican values of

private property, individualism and small community but who were

almost condemned to disappear in the wake of France’s economic

evolution in the post-war era. Depending on your perspective, the

instinctive conservatism of yesteryear had perhaps been

transformed into a reactionary movement, violent reaction to a

‘natural evolution’ of things.

For

Poujade and the UDCA, the culprits were the same: the big businesses

and corporate leaders, le

fisc,

the revolutionary trade unions, the left and its anti-individualism,

the corrupt parliament and the regime of parties, foreigners and all

those who were “selling off” France and its empire (especially

Algeria); all with a dose of conspiratorial antisemitism,

attacking the Jews who allegedly owned the big business and big

retailers but also thinly veiled jabs at Pierre Mendès France’s

Jewish faith.

The

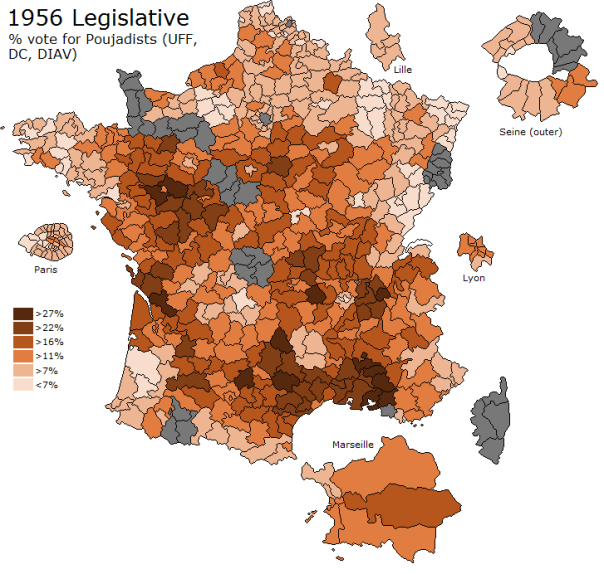

surprise of the January 1956 was the Poujadist movement, whose lists

(Union

et fraternité française,

UFF or UDCA etc) won 51 seats and some 11.5% of the popular vote. The

map below shows the results of Poujadists by 1936 constituency.

Gray

departments had no Poujadist lists.

For

those of us used to the tidy and orderly map of the French far-right

in its FN incarnation, the first thought which comes to mind upon

seeing this map is a very puzzled “what the hell is this mess?”

Indeed, when we’re used to the tidy map of the FN and its bases

east of the Le Havre-Valence-Perpignan line, this map is

an disorderly mish-mash of colours all over the place with

little pattern. What is even more puzzling is that the Poujadists,

oft called the ancestor of the FN – with reason – should have a

map which is diametrically different from that of the far-right as we

would learn to know it some 30 years later. The Poujadists are almost

totally absent from a line going from Le Havre to Belfort, where the

FN today flexes its muscles the best. Certainly some of the Poujadist

strongholds such as the Vaucluse, Gard and Hérault have always given

the FN strong showings, but other strong points – Maine-et-Loire,

Charente-Maritime, Indre-et-Loire, Deux-Sèvres, Aveyron, Gers and

even Isère to an extent – are not places where the FN does

particularly well.

The

most basic explanation for the Poujadist’s success would be to

conclude that they simply took the succession of the Gaullists. It is

not a ridiculous proposition. The RPF in 1951 and the Poujadists in

1956 both appealed to a certain conservative anti-system and

anti-regime vote – both were in direct opposition to the Fourth

Republic and the rhetoric of the Poujadists in 1956 vis-a-vis the

‘regime of the parties’ and the anti-parliamentarianism were

quite similar to the Gaullist rhetoric of 1951 which targeted the

regime of the parties. A cursory look at the raw statistics leads us

to the same conclusion: besides the MRP, all other major forces (PCF,

SFIO, Radicals, moderates) maintained or built on their 1951

electorates in 1956. The MRP only fell from 12.5% to a bit less than

11%, and the MRP had little in common with the Poujadists. However,

the Gaullists won 21.7% in 1951 but their successors in 1956 won

4.5%. The far-right and Poujadists won 12%. We could conclude, pretty

easily, that while not all Gaullists voted Poujadist, most Poujadists

had voted Gaullist some four years prior.

Problem

solved? No, we’ve only dug ourselves into a hole. If you remember

the 1951 map of the RPF’s strength, we had seen that its bases had

been concentrated almost quasi-entirely in northern France or what

was occupied France in 1941. It had been absent from the bulk of

southern France. In contrast, the Poujadists were more geographically

spread out but they had their big strongholds (Vaucluse, Hérault,

Gard, Aveyron) in southern France and only the Maine-et-Loire was a

stronghold of the RPF and Poujadists. It is possible and even logical

that the Poujadists received the support of many voters who had voted

RPF in 1951. But like Boulanger in 1889, Poujadism cut vertically

across all established

political parties. He even took left-wing votes. In most cases, the

main victims of Poujadism were the right. The return of Gaullist

voters to their traditional right-wing (moderate, MRP) roots likely

hide compensated loses to the Poujadists.

There

were, after all, key differences between Gaullism and Poujadism.

Gaullism, through its leading figure, appealed widely to a certain

conservative electorate, through its emphases on order, hierarchy and

stability. Through its historical roots, it likely appealed very much

to those who had been the fiercest of résistants during

the War. On the other hand, Poujadism did not have a similar appeal

to a conservative electorate fond of order and stability but rather

appealed to another electorate, this one either apolitical or weakly

politicized, anti-parliamentarian in its sympathies and quite keen to

Poujadism populism and nationalism. In addition, often derided as

fascist (and its leader as ‘Poujadolf’), the Poujadists were more

likely to appeal to those more supportive of the Vichy regime and its

traditionalist, “old France” rhetoric. Finally, Gaullism was in

some ways a right-wing reformist movement in 1951 despite its

Bonapartist overtones, it appealed to modern and industrial France.

Poujadism was in many ways reactionary, the last-straw defense of a

drowning type of old and traditional France. It had little in its

rhetoric to appeal to modern and industrial France.

Poujadism

through its roots in the UDCA and Pierre Poujade carried a

distinctive appeal to shopkeepers and merchants. I think it quite

fair to assume that most shopkeepers and merchants voted Poujadist.

For curiosity’s sake, I attempted to compare the Poujadist vote by

department in 1956 to the percentage of artisans,

commerçants et chefs d’entreprises in

each department in 1968 (the earliest I have departmental census data

for). It isn’t perfect, the two data sets being 12 years apart, but

the general pattern in terms of distribution of artisans/commerçants

can be reasonably expected to have been similar in 1956. In

general, there seems to be a general increase in Poujadist votes as

the weight of artisans/commerçants increases. But there are some big

outliers: the best Poujadist department (Vaucluse, 22.5%) had only

12.3% of shopkeepers and merchants in 1968. Similarly, the highest

percentage of shopkeepers and merchants in 1968 (Alpes-Maritimes,

16.2%) gave the Poujadists only 7.3. I calculated the correlation

coefficient to be 0.31, indicating a very weak medium positive

correlation. It is even stranger when you take only departments with

over 12% of artisans/commerçants in 1968, the correlation is

actually negative:

-0.35! In those with over 13% of artisans/commerçants, there is a

strong negative correlation

again: -0.68.

While

it likely that a good number of Poujadist voters were small or medium

business owners in small towns in rural ‘declining’ France, its

success cannot be explained solely by that factor. In

departments where the Poujadists did least well, it is likely that

their success was largely limited to the UDCA’s base social

category. But the Poujadist success was built on a heterogeneous base

of support, especially in the Midi and the centre-west. By its form

as a conservative populist reaction to rapid industrialization and

“aggressive capitalism”, the Poujadist rhetoric was not only

a sectional message designed for one social group, namely

shopkeepers.

Besides

the growth of mass retail and large commercial surfaces, the other

victim of deflation post-1953 were small landholders – agriculteurs

exploitants. Small

landholders, owning and cultivating their own parcel of land, were

the product of the Revolution and the rural bedrock of the Republic

in the 1870s. Like shopkeepers, small landholders were not

particularly affluent but by their ownership of land they were (in

most cases) instinctively conservative and deeply attached to the

republican values of private property. But like shopkeepers, they

were the ‘forgotten’ victims left behind by economic

modernization.

Inflation

had been advantageous for farmers who had gotten artificially rich.

Deflation brought along a massive drop in prices, and thus a loss in

revenue for farmers. Inflation had been advantageous for farmers not

only because they got rich but also because it had provided them with

the revenue to pay for expensive new, modern machinery. The drop in

prices post-1953 meant that this revenue dried up, and small

landholders found themselves struggling to continue the ‘silent

revolution’ in French agriculture. In many cases, this sped up the

(inevitable?) decline of small property and the amalgamation of

several unviable small properties into larger,

modernized exploitations.

Owners

of small family farms and small business owners, had, in many cases,

many shared common interests even beyond politics. In a small town

feeling, they knew each other and were allied and linked to each

other. In a certain sense, one’s destiny impacted the other’s

destiny and they were perhaps even liked to a certain extent.

Poujadism should not be understood solely in terms of a single class’

defensive reaction, which it was in part, but as being a broader

movement of resistance to economic modernization. André Siegfried

had talked about Poujadism as being a rear-guard’s defensive

reaction pitting rural peasant against cities, the province against

Paris, the artisans against factories, of regions in decline against

booming neo-industrial regions and of the individual against “an

invading socialist state”.

No

surprise then that Poujadism viewed in those terms would carry an

equally as powerful appeal to those who in 1956 suffered a plight

similar to that of the shopkeeper. In the Orléanais, the Beauce

and the Brie, Poujadism appealed to rural workers in the wheat basket

of the country. In the Berry and parts of Champagne, Poujadism

appealed to poor peasants in declining regions with an outdated

agricultural economy. In a region stretching from continental

Brittany to the Anjou, Poitou and Charentes, Poujadism broke

cleavages such as the all-important religious cleavage to appeal to

regions where rural poverty was everywhere a reality, mixed in (in

certain cases) with a local base of shopkeepers.

In

the Languedoc and especially the Vaucluse, the strength of Poujadism

was furthered by the local crisis in the wine industry which

swelled the ranks of the discontent. The Poujadists, judging simply

from an unscientific inductive observation of the map, seem to have

enjoyed some success with wine growers in the Loire valley, the

Bordelais and Beaujolais but far more limited success with those in

Bourgogne and Champagne.

So

far we have added one variable to our explanation besides

shopkeepers, which had a 0.31 correlation. We have added the variable

of revenue. Measured against the individual average revenue in each

department in 1951 (measured with France being 100, and departments

being either above or below 100 based on individual revenue), we find

a negative correlation of -0.27, indicating that Poujadists did

better in departments with lower individual revenue. But the

correlation is rather weak.

I

n some isolated areas like the Aveyron, the Alps or Isère,

Poujadism was a reaction of ‘regions in decline’ as Siegfried had

noted. The Aveyron’s population declined by 4.9% between 1946 and

1954, and the Poujadists (18.8% of registered voters in the

department) did best in those more mountainous areas who

suffered the highest decline. In taking only those departments whose

population declined between 1946 and 1954, the correlation between

population decline and Poujadist vote is 0.53, a pretty strong

correlation. But it is not universal: Lozère had the steepest

decline at -9% yet the Poujadists won only 8% of the vote. The Cantal

and Haute-Loire both declined by more than the Aveyron, but had

weaker Poujadist results (11%). Local factors, some of them political

such as other incumbents, lists and the strength of the Poujadist

slate must be considered.

Isère

is a particularly interesting department. Its population grew by 9%

between 1946 and 1954, and it was quite industrialized, yet the

Poujadists did particularly well with 15% of the vote (registered

voters). Isère’s population growth and industrialization in that

era was widely seen as being particularly rapid and regionally

uneqal. It came mostly to the benefit of Sud Isère and the

Grenoble region, and to a lesser extent the industrial centres of the

Nord Isère in proximity to Lyon. It left behind declining rural

regions lying between the two urban centres of attraction of

Lyon-Vienne-Bourgoin and Grenoble.

The

overall correlation between population change and Poujadist vote is

weak but negative (as expected) at -0.26. The link between

industrialization, as measured by employment in industry or

transportation in 1951, and the Poujadist vote is more significant

and negative (as expected) at -0.35.

Poujadism,

born as anti-parliamentary movement, was perhaps ultimately unable to

survive the contradiction between its aim and founding value

(anti-parliamentarianism) and being a parliamentary actor. Its

emergence as a last-straw reaction to industrialization and

modernization which would only intensify in the 1960s precluded it

from being anything more than a temporary feu

de paille (flash

in the pan) in the realm of French politics. The emergence of the

Fifth Republic and the shift away from the

parliamentary partitocratie killed

off a lot of the movement’s anti-institutional and anti-system

rhetoric. Gaullism would re-emerge as an attractive and viable

political option a bit more than two years later. The only thing left

of Poujadism, it seems, is the use of “Poujadist” as a blanket

term for most populisms of that kind.

But

despite it going down in history as a feu

de paille,

as a curiosity of history but ultimately a futile and quixotic

single-issue movement, Poujadism has had a deeper impact on French

politics and the far-right in France. Not only because Jean-Marie Le

Pen was elected as a young UFF deputy for the Seine in 1956. The

rhetoric behind Poujadism with the attacks on the corrupt political

establishment, the big corporations, the foreign profiteers,

aggressive nationalism and part of wider movement which appealed to

those who felt ‘forgotten’ by the political elites and those who

fell behind economically. What is pejoratively called the petite

bourgeoisie,

or more specifically the shopkeepers and merchants who formed the

backbone of the UDCA, have remained one of the FN’s backbones

though the FN has never been as closely identified to that social

category as the Poujadists were and their influence on the modern FN

is fading, though certainly present. To a good extent, the FN has won

votes from voters who are neither part of the unionized working-class

or the wealthier upper middle-classes, and who are at odds both with

the traditional right in its old elitist Orleanist incarnations and

with the left in its old traditional sense described, by Poujadists,

as ‘anti-individualists’. I think the FN vote in places like

rural and exurban Champagne, Bourgogne and Picardie are quite

reflective of a rural, “forgotten” electorate which is not

particularly well-off and gets put off by both the right and the

left. Not working-class in the industrial sense, but of some small

town working-class tradition. These particular types of people might

not have voted Poujadist in 1956 (although some certainly did), but I

feel that the rhetoric which appeals to them on the FN’s behalf is

similar to the Poujadist rhetoric of 1956.

Pierre

Poujade quickly broke with his young MP, and disavowed any links

between his movement and the FN. Poujade was not a politician, he was

far more of a corporatist unionist with a talent for oratory. But his

movement had deep repercussions on the FN in terms of ideology and

orientation. The Poujadist vote in 1956 was remarkable for its

strength and its homogeneity across the country, but in the details

the Poujadist vote is also remarkable for its composition’s

heterogeneity. In almost each region, it seems as if the makeup of

the vote was different and as if the impetus to vote for Pierre

Poujade’s movement varied significantly from region to region: wine

crisis here, population decline there, shopkeepers and merchants

angers there, falling behind on industrialization here, structural

rural poverty there. Despite its short life as a political movement

and regardless of whether you have a positive or negative view of

Poujade and his movement, Poujadism had a deep impact on the French

far-right after 1945.

No comments:

Post a Comment