This is personal. It started when I was about eight years old. I was walking on Farm Street in Hockley, Birmingham, where my family lived. I was in my own little world, having poetic thoughts and wondering what the future held for me.

Then, bang, I felt an almighty slap on the back of my head and I fell to the floor. A boy had hit me with a brick as he rode past on his bicycle. As I lay on the ground with blood pouring from the back of my head, he looked back and shouted: “Go home, you black bastard.” I had no idea what he was talking about. I was going home. Who was black? What was a bastard?

At home my mother sat me down and explained to me that there were some people in this country that didn’t like people who were not white, and they wanted us to go back home. I spent the next few months wondering where my “real” home was – I thought it was in Birmingham – and what was so great about being white, and why would anyone want to hit someone because of the colour of their skin?

I was growing up confused, but a couple of years later I felt the need to show my independence and spend some time away from my family, so I decided to visit my local youth club.

The game of choice for young boys back then was table tennis, a game that I had played a few times and was quite good at. When I arrived at the centre I went straight to the table-tennis table and watched a few games; then I plucked up the courage and asked if I could play. I was quickly surrounded by a group of young boys and girls who started pushing me towards the door and telling me that black people should not come to this club. I was pushed and tripped to the floor a couple of times but I was relieved to see an adult arrive on the scene and come to my rescue. But he wasn’t much help. He did tell the mob to leave me alone, and then he took me into his office, where he told me that it would be best if I didn’t come back to the youth club because I would upset the atmosphere. He said they were like a family at the club, and I should find a family of my own.

These are just two examples of the racism that I experienced as a very young boy. I understood very quickly that I had to grow up tough and that I had to always be on the lookout for strangers who hated me and anyone like me. For the next few years I suffered many racist attacks, but I became streetwise. I learned boxing and kung fu so I could look after myself. But there was not much I could do when I was surrounded by 20 of them, and there was not much I could do when the perpetrators were the police. The police brought another level of difficulty to my life, but that’s another story.

In order to escape the unemployment, the “thug life” and the West Midlands police force, in 1979 I left Birmingham and headed to London. I found myself in Leyton, east London, which looked very much like the community I had left in Birmingham: working-class white people, who on the whole were enjoying the benefits of a multicultural community. The music of youth then was punk, reggae, ska and soul. Street and park festivals were popular, and (on the whole) the attitude of youth was that we had to stick together in order to overcome the miseries of unemployment, and music was a great way of bringing us together. But it didn’t take long for me to realise that there were two big issues that we had to deal with day after day, and night after night: the police, who had something called the “sus” law that they used to use against us, and the National Front. National Front members tended to have low-cut or shaved hair, rolled-up jeans and steel-capped boots, and they made no attempt to hide the fact that their main purpose was to rid the country of foreigners. They would roam the streets and viciously attack people who weren’t like them. They would often crash our clubs and cause destruction, or they would wait until we left the clubs, follow us for a while, and then attack. There were many times when I had to fight my way out of clubs, or fight my way home, but one of the most violent attacks I ever witnessed happened one night at Stratford Broadway in east London.

Stratford was a place that was proud of its multicultural makeup. I felt safe there, although I knew that not far away there were no-go areas for black people. Barking and Canning Town were places we were told never to visit. They were National Front strongholds and the racists there clearly marked their boundaries.

Canning Town was adjacent to Stratford, where one hot, sticky night I was walking home as slowly as I could. I noticed a couple waiting for a bus who looked as if they were passionately in love. They hugged and kissed so much that I had to lower my gaze in embarrassment. After one long kiss the bus arrived and to my surprise the boy got on the bus, leaving the girl to walk home. I know it was sexist to assume that it was the boy walking the girl to the bus stop, but that was me back then; I was learning. As the girl began to walk away, skinheads (from Canning Town) began to emerge from every nearby shop doorway. They surrounded the girl, calling her a “nigger lover” and a “slag”; they kicked her to the ground and continued to kick her, until I and another passerby intervened. Intervened might be too strong a word; we distracted them just enough to allow the girl to get up and run away, but in the process we got quite a kicking ourselves.

a police cordon, east London, 1979. Photograph: Rolls Press/Popperfoto/Popperfoto/Getty Images

What really struck me about this incident was the viciousness of the attack. Strong young men, ranging in age from 16 to 30, kicking, punching and stamping on a girl who was no older than 18. She was white like them, but they hated her because of her love for a black man. Each one of them was filled with hatred for someone they had never met, and someone who could have been related to one of them. They hated us, and they hated anyone who didn’t hate us, and they had even more hatred for anyone who would dare to love us.

As a young Rastafarian I was taught not to hate, and it wasn’t in my nature to hate – after all, we were listening to music that was all about peace and love and bringing people together. We wanted to be living examples of how people could live together, but we knew that if we did nothing we would be killed on the streets. We knew that the National Front was a Nazi front, so our slogan became “Self-defence is no offence”, and we meant it. To defend ourselves in local communities up and down the country, black and Asian groups organised self-defence groups. These were people who would spring into action, defending (when possible) anyone who was attacked.

In London, we had a group called Red Action, a bunch of leftwingers who operated like an alternative police force. They would come to clubs and gatherings and make sure that the event was not invaded and that people got home safely. There were no mobile phones so they would communicate with each other using walkie-talkies, and they would react to our distress calls much quicker than Her Majesty’s police force.

Then there was the legendary Sari Squad. These were women, mainly of south Asian origin, who were experts in various martial arts and ready and willing to take on any racists who would try to spoil our fun. They fought with style, and would usually burst into song after seeing off any attackers.

The National Front did not hide their bigotry. They chanted racist songs, they praised fascist heroes and they did Nazi salutes; but then something strange happened. A schism appeared. They had put up candidates in elections before, but now a group within the “movement” thought that they should seek more respectability and concentrate their efforts on becoming a real political party by seeking power through the ballot box. We still had to fight them on the streets. But now some of them had begun wearing suits and appearing on television programmes.

They even made party political broadcasts, which some argued was a major contributor to their downfall. They were a great example of a political party with no intellectual base at all. We knew that in order to make Britain more British they planned to get rid of immigrants, but now we also knew that to cut crime they were going to get rid of immigrants, to save the National Health Service they were going to get rid of immigrants, to bring inflation down they were going to get rid of immigrants, to get the traffic moving they were going to get rid of immigrants, and to improve the British weather they were going to get rid of immigrants. It was the only idea they had. The National Front continued to argue among themselves about how racist they should be and where they should concentrate their racism, and as they did so their membership began to wane.

And so Combat 18 and the British National Party (BNP) began to grow. For a while the popular face of racism was the BNP, but then they lost their thunder, and then came the UK Independence Party (Ukip) and the English Defence League (EDL). This is not a subject I studied; I was only interested in all this because I was a writer and commentator, so there were times when I would have to confront their members on TV debates, but – I’m going to repeat myself – we still had to fight them on the streets. When the racists were busy changing their names and public personas, the majority of their victims weren’t concerned with what they were calling themselves. When they were deciding whether or not they should be wearing suits or boots, we were not considering how we should dress in response; we were still fighting for our lives on the streets. At various times we were being told by the racists that their enemies were the “Pakis”, or “Jamaican yardies”, or the “Islamic fundamentalists”, but whatever they say, whatever they call themselves, they have been attacking the same people on the streets, and we (those same people) still have to fight them on the streets. Nothing much has changed.

I have drawn strength and inspiration from the many people who have stood up to the racist thugs and defended our freedom to walk the streets over the years. When the police would not take attacks on black people seriously, allowing gangs of racists to roam the streets, hunting us down, and when those same police drew inspiration from a government that accused immigrants of swamping Britain, we were left to ourselves. There are many unsung heroes who really did put their lives on the line in our struggle. Some died in action, and we must always remember them. There are no monuments to them, there is no state recognition of them, but they are true martyrs. But I am saddened by some of the people who fought the racists that have now become part of the establishment; at best they tolerate racism by the establishment, at worst they become a part of it.

Many became part of what was called “the race industry”. They were skilled in applying for grants and starting projects, or they were skilled at positioning themselves to get the “good” jobs in the booming “race industry”. This is not a criticism of them; I just want to make the point (again) that when they were doing all that, we were still fighting them on the streets. Blair Peach, Stephen Lawrence, Anthony Walker or the girl I saw being beaten in Stratford were not in meetings when they were attacked; they were not applying for grants or running for parliament when they were attacked; they were all walking the streets.

I have to agree with those who claim that the political elite has neglected the white working class. There are poor white people living in ghettoes all over Britain, they live in terrible housing conditions, their traditional industries have been destroyed, their schools are being run down, and governments of all colours have been ignoring their cries for help for decades. It’s true. What is also true is that there are poor black people living in ghettoes all over Britain. They also live in terrible housing conditions, their traditional industries have been destroyed, their schools are being run down, and governments have been ignoring their cries for help since the creation of the slave trade and the building of the British empire.

It is precisely for these reasons that I have always thought that these poor white people and these poor black people should unite and confront the people who oversee all of our miseries. It is classic divide and rule. The biggest fear of all of the mainstream politicians is that we all reach a point where we understand how much we have in common and, instead of turning on ourselves, we turn on them. In poetry and prose I have said that unity is strength, and that we should get to a point where we are not talking about black rights or white rights, Asian rights or rights for migrant workers; we are just talking about our rights. As long as people of colour and minority groups are seen as the other, as long as we are being blamed for all of society’s ills (including too many cars on our roads), we will keep trying to get our politicians to be honest, and we will continue to call on the white working classes to unite with us. But, if they don’t, we will still have to fight racists on the streets. This is personal.

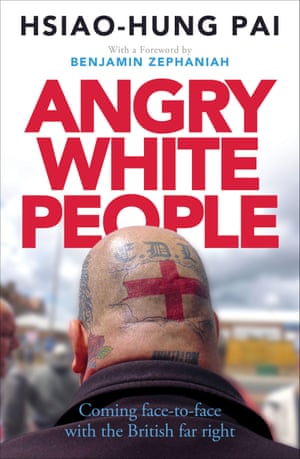

Extracted from the introduction to Angry White People: Coming face-to-face with the British far right, by Hsiao-Hung Pai,

No comments:

Post a Comment