I think I have been dyslexic all of my life. I remember in 1968 having my legs smacked by Miss Serank for getting my letters the wrong way around. I font think that English Prep schools figured it out . The key to the solution has ale=ways been my imagination and my ability to ask “What if?” . Its made me an avid reader of books, particularly Science fiction and fantasy. Its made me able to understand James Joyce and Virginia Woolf as well as William Faulkner and the streams of consciousness approach of William James,

Its also helped me think

metaphorically and symbolically/ I think in many ways its helped me

think outside of the box. Its made me a rebel and a challenge of

systems and oddly I am very grateful for the gift it has given me,

One of the things that has made me

laugh is that when you are winning an argument on social media then

the last refuge of the narrow minded conservative is to reply about

spelling. What is fascinating is that the more conservative they are

then the worse is their imagination and their creativity. Its rather

like saying I have nothing say, nothing to contribute in originality

and are the most obsessed with the the correctly s pelt words whilst

having the least to say/. Perhaps it is the inability to think

outside the box. Anyway I found this fascinating article from the

Scientific American. It has great resonance with me.

Those who read my posts as I travel

in to work must sometimes wonder exactly what I am saying. I usually

correct it with Word once I get to work but a few things will always

slip through. Spelling is immensely important but too often the

critics of those who are mildly dyslexic are often ise this approacj

a defence mechanism of the critic`s conservatism and imaginative

ability. However these cases are few in number and I take great

pleasyre in pointing this out.

It with my poor sight has given me a

first class memory and an inability unfortunately at times the

inability to deal with ignorance and stupidity. So it gets me into

trouble regularly. Anyway first please read about Leonardo Da Vinci

and then on to the Advantages of Dyslexia

15 April 1452 – 2 May 1519

Inventor, Painter, Designer, Musician -"Renaissance Man"

Leonardo da Vinci was an

inventor, painter, and sculptor whose broad interests also

included architecture, science, music, mathematics, engineering,

literature, anatomy, geology, astronomy, botany, writing, history,

and cartography.

Art historian Helen Gardner wrote that the

scope and depth of his interests were without precedent in recorded

history, and “his mind and personality seem to us superhuman”.

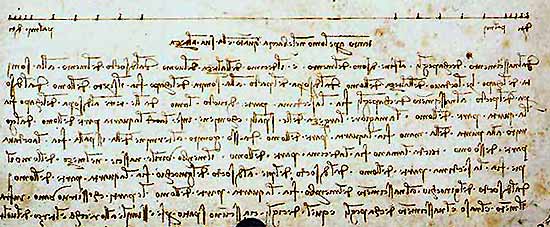

One remarkable indication that Leonardo was

dyslexic is in his handwriting. Leonardo was constantly sketching out

his ideas for inventions. Most of the time, he wrote his notes in

reverse, mirror image:

Although unusual, this is a trait sometimes shared

by other left-handed dyslexic adults. Most of the time, dyslexic

writers are not even consciously aware that they are writing this

way; it is simply an easier and more natural way for them to write.

Leonardo’s spelling is also considered erratic

and quite strange. He also started many more projects then he ever

finished – a characteristic now often associated with

attention deficit disorder (ADHD).

However, when it came to his drawing and artwork,

Leonardo’s work is detailed and precise.

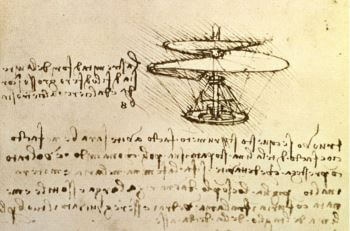

Leonardo

was intrigued with the concept of human flight, and spent many years

toying with various ideas for flying machines. When he drew his

flying machine, he wrote (backwards, of course): “A small model can

be made of paper with a spring like metal shaft that after having

been released, after having been twisted, causes the screw to spin up

into the air.”

Leonardo

was intrigued with the concept of human flight, and spent many years

toying with various ideas for flying machines. When he drew his

flying machine, he wrote (backwards, of course): “A small model can

be made of paper with a spring like metal shaft that after having

been released, after having been twisted, causes the screw to spin up

into the air.”

His extraordinary art work and inventive genius

are proof that he truly possessed the gift of dyslexia.

Artwork:

- Mona Lisa

- The Last Supper

- Virgin of the Rocks

- St.John the Baptist

- The Virgin and Child with St. Anne

Inventive Designs:

- Leonardo’s Robot (mechanical knight)

- Helicopter (Aerial Screw)

- Parachute

- Ornithopter

- Mechanical Adding Machine

- Diving Suit

- Steam Cannon

- Machine Gun

- Armored Tank

The Advantages of Dyslexia

Impossible "Waterfall" Credit:

"Escher Waterfall". Via Wikipedia

“There are three types of mathematicians, those

who can count and those who can’t.”

Bad joke? You bet. But what makes this amusing is

that the joke is triggered by our perception of a paradox, a

breakdown in mathematical logic that activates regions of the brain

located in the right

prefrontal cortex. These regions are sensitive to the perception

of causality and alert us to situations that are suspect or fishy —

possible sources of danger where a situation just doesn’t seem to

add up.

Many of the famous etchings by the artist M.C.

Escher activate a similar response because they depict scenes that

violate causality. His famous “Waterfall”

shows a water wheel powered by water pouring down from a wooden

flume. The water turns the wheel, and is redirected uphill back to

the mouth of the flume, where it can once again pour over the wheel,

in an endless cycle. The drawing shows us a situation that

violates pretty much every law of physics on the books, and our brain

perceives this logical oddity as amusing — a visual joke.

The trick that makes Escher’s drawings

intriguing is a geometric construction psychologists refer to as an

“impossible

figure,” a line-form suggesting a three-dimensional object that

could never exist in our experience. Psychologists, including a team

led by Catya von Károlyi of the University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire,

have used such figures to study

human cognition. When the team asked people to pick out impossible

figures from similarly drawn illustrations that did not violate

causality, they were surprised to discover that some people were

faster at this than others. And most surprising of all, among those

who were the fastest were those with dyslexia.

Dyslexia is often called a “learning

disability.” And it can indeed present learning challenges.

Although its effects vary widely, children with dyslexia read so

slowly that it would typically take them a half a year to read

the same number of words other children might read in a day.

Therefore, the fact that people who read so slowly were so adept at

picking out the impossible figures was a big surprise to the

researchers. After all, why would people who are slow in reading be

fast at responding to visual representations of causal reasoning?

Though the psychologists may have been surprised,

many of the people with dyslexia I speak with are not. In our

laboratory at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics we have

carried out studies funded by the National Science Foundation to

investigate talents

for science among those with dyslexia. The dyslexic scientist

Christopher Tonkin described to me his sense of this as a sensitivity

to “things out of place.” He’s easily bothered by the

weeds among the flowers in his garden, and he felt that this

sensitivity for visual anomalies was something he built on in his

career as a professional scientist. Such differences in

sensitivity for causal perception may explain why people like Carole

Greider and Baruj

Benacerraf have been able to perform Nobel prize-winning science

despite lifelong challenges with dyslexia.

In one study,

we tested professional astrophysicists with and without dyslexia for

their abilities to spot the simulated graphical signature in a

spectrum characteristic of a black hole. The scientists with dyslexia

—perhaps sensitive to the weeds among the flowers— were better at

picking out the black holes from the noise, an advantage useful in

their careers. Another study

in our laboratory compared the abilities of college students with and

without dyslexia for memorizing blurry-looking images resembling

x-rays. Again, those with dyslexia showed an advantage, an advantage

in that can be useful in science or medicine.

Why are there advantages in dyslexia? Is it

something about the brains of people with dyslexia that predisposes

them to causal thinking? Or, is it a form of compensation,

differences in the brain that occur because people with dyslexia read

less? Unfortunately, the answer to these questions is unknown.

One thing we do know for sure is that reading

changes the structure of the brain. An avid reader might read for an

hour or more a day, day in and day out for years on end. This highly

specialized repetitive training, requiring an unnaturally precise,

split-second control over eye movements, can quickly restructure the

visual system so as to make some pathways more efficient than the

others.

When illiterate adults were taught to read, an

imaging study

led by Stanislas Dehaene in France showed that changes occurred in

the brain as reading was acquired. But, as these adults developed

skills for reading, they also lost their former abilities to process

certain types of visual information, such as the ability to determine

when an object is the mirror

image of another. Learning to read therefore comes at a cost,

and the ability to carry out certain types of visual processing are

lost when people learn to read. This would suggest that the visual

strengths in dyslexia are simply an artifact of differences in

reading experience, a trade-off that occurs as a consequence of poor

reading in dyslexia.

My colleagues and I suggested

that one reason people with dyslexia may exhibit visual talents is

that they have difficulty managing visual attention. It may at

first seem ironic that a difficulty can lead to an advantage, but it

makes sense when you realize that what we call “advantages” and

“disadvantages” have meaning only in the context of the task that

needs to be performed.

For example, imagine you’re looking to hire a

talented security guard. This person’s job will be to spot things

that look odd and out of place, and call the police when something

suspicious —say, an unexpected footprint in a flowerbed— is

spotted. If this is the person’s task, would you rather hire a

person who is an excellent reader, who has the ability to focus

deeply and get lost in the text, or would you rather hire a person

who is sensitive to changes in their visual environment, who is less

apt to focus and block out the world?

Tasks such as reading require an ability to focus

your attention on the words as your eyes scan a sentence, to quickly

and accurately shift your attention in sequence from one word to the

next. But, to be a good security guard you need an opposite

skill; you need to be able to be alert to everything all at once, and

though this isn’t helpful for reading, this can lead to talents in

other areas. If the task is to find the logical flaw in an impossible

figure, then this can be done more quickly if you can distribute your

attention everywhere on the figure all at once. If you tend to focus

on the visual detail, to examine every piece of the figure in

sequence, it could take you longer to determine whether these parts

add up to the whole, and you would be at a disadvantage.

A series of studies

by an Italian team led by Andrea Facoetti have shown that

children with dyslexia often exhibit impairments in visual attention.

In one study,

Facoetti’s team measured visual attention in 82 preschool children

who had not yet been taught to read. The researchers then waited a

few years until these children finished second grade, and then

examined how well each child had learned reading. They found that

those who had difficulty focusing their visual attention in preschool

had more difficulty learning to read.

These studies raise the possibility that visual

attention deficits, present from a very early age, are responsible

for the reading challenges that are characteristic of dyslexia. If

this theory is upheld, it would also suggest that the observed

advantages are not an incidental byproduct of experience with

reading, but are instead the result of differences in the brain that

were likely present from birth.

If this is indeed the case, given that attention

affects perception in very general ways, any number of advantages

should emerge. While people with dyslexia may tend to miss

details in their environment that require an attentional focus, they

would be expected to be better at noticing things that are

distributed more broadly. To put this another way, while

typical readers may tend to miss the forest because it’s view is

blocked by all the trees, people with dyslexia may see things more

holistically, and miss the trees, but see the forest.

Among other advantages observed, Gadi Geiger and

his colleagues at MIT found

that people with dyslexia can distribute their attention far more

broadly than do typical readers, successfully identifying letters

flashed simultaneously in the center and the periphery for spacings

that were much further apart. They also showed

that such advantages are not just for things that are visual, but

that they apply to sounds as well. In one study, simulating the

sounds of a cocktail party, they found that people with dyslexia were

able to pick out more words spoken by voices widely-distributed in

the room, compared with people who were proficient readers.

Whether or not observations of such advantages

—measured in the laboratory— have applications to talents in real

life remains an open question. But, whatever the reason, a clear

trend is beginning to emerge: People with dyslexia may exhibit

strengths for seeing the big picture (both literally and

figuratively) others tend to miss. Thomas G. West has long

argued that out-of-the-box thinking is historically part and

parcel of dyslexia, and more recently physicians Brock

and Fernette Eide have advanced similar arguments. Sociologists,

such as Julie Logan of the Cass Business School in London agree.

Long ago I found

that dyslexia is relatively common among business entrepreneurs;

people who tend to think differently and see the big picture in

thinking creatively about a business.

Whatever the mechanism, one thing is clear:

dyslexia is associated with differences in visual abilities, and

these differences can be an advantage in many circumstances, such as

those that occur in science, technology, engineering and mathematics.

In physics we know that an engine is capable of productive work only

when there are differences in temperature, hot versus cold. It’s

only when everything is all the same that nothing productive can get

done. Neurological differences similarly drive the engine of society,

to create the contrasts between hot and cold that lead to productive

work. Impairments in one area can lead to advantages in others, and

it is these differences that drive progress in many fields, including

science and math. After all, there are probably many more than three

kinds of mathematicians, and society needs them all.

Are you a scientist who specializes in

neuroscience, cognitive science, or psychology? And have you read a

recent peer-reviewed paper that you would like to write about? Please

send suggestions to Mind Matters editor Gareth

Cook. Gareth, a Pulitzer prize-winning journalist, is the series

editor of Best American Infographics

and can be reached at garethideas AT gmail.com or

Twitter @garethideas.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR(S)

Matthew H. Schneps is an

astrophysicist with dyslexia who founded the Laboratory for Visual

Learning to investigate the consequences of cognitive diversity on

learning. He is a professor of computer science at UMass Boston, and

conducts research in dyslexia at the Harvard Graduate School of

Education. Currently, Schneps is writing a book on how the emergence

of e-reading technologies is redefining dyslexia.

No comments:

Post a Comment